Travel Tales: Pitcairn Island

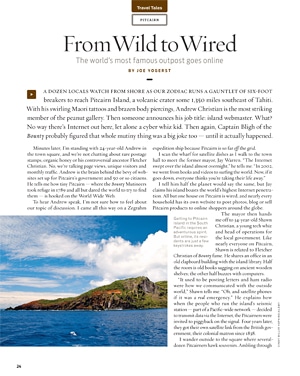

A dozen locals watch from shore as our Zodiac runs a gauntlet of six-foot breakers to reach Pitcairn Island, a volcanic crater some 1,350 miles southeast of Tahiti. With his swirling Maori tattoos and brazen body piercings, Andrew Christian is the most striking member of the peanut gallery. Then someone announces his job title: island webmaster. What? No way there's Internet out here, let alone a cyber whiz kid. Then again, Captain Bligh of the Bounty probably figured that whole mutiny thing was a big joke too — until it actually happened.

Minutes later, I'm standing with 24-year-old Andrew in the town square, and we're not chatting about rare postage stamps, organic honey or his controversial ancestor Fletcher Christian. No, we're talking page views, unique visitors and monthly traffic. Andrew is the brain behind the bevy of websites set up for Pitcairn's government and 50 or so citizens. He tells me how tiny Pitcairn — where the Bounty Mutineers took refuge in 1789 and all but dared the world to try to find them — is hooked on the World Wide Web.

To hear Andrew speak, I'm not sure how to feel about our topic of discussion. I came all this way on a Zegrahm expedition ship because Pitcairn is so far off the grid. I scan the wharf for satellite dishes as I walk to the town hall to meet the former mayor, Jay Warren. "The Internet swept over the island almost overnight," he tells me. "In 2002, we went from books and videos to surfing the world. Now, if it goes down, everyone thinks you're taking their life away."

I tell him half the planet would say the same, but Jay claims his island boasts the world's highest Internet penetration. All but one house on Pitcairn is wired, and nearly every household has its own website to post photos, blog or sell Pitcairn products to online shoppers around the globe.

The mayor then hands me off to 34-year-old Shawn Christian, a young tech whiz and head of operations for the local government. Like nearly everyone on Pitcairn, Shawn is related to Fletcher Christian of Bounty fame. He shares an office in an old clapboard building with the island library. Half the room is old books sagging on ancient wooden shelves; the other half buzzes with computers.

"It used to be posting letters and ham radio were how we communicated with the outside world," Shawn tells me. "Oh, and satellite phones if it was a real emergency." He explains how when the people who run the island's seismic station — part of a Pacific-wide network — decided to transmit data via the Internet, the Pitcairners were invited to piggyback on the signal. Four years later, they got their own satellite link from the British government, their colonial matron since 1838.

I wander outside to the square where several-dozen Pitcairners hawk souvenirs. Ambling through the stalls, they sell all kinds of wares — walking canes, Pitcairn flags, locally harvested honey, scale models of the Bounty — and each touts website URLs too. But the Internet sales come with a caveat. "People don't read the fine print," Brenda Christian says rising from her stall. "I get e-mails all the time saying, 'It's been two weeks and I haven't got my honey yet.' I tell 'em to go back and check the part of my website where it says it could take up to six months to get your order."

The reason? Orders are conveyed by cargo ship to New Zealand, then dispatched to the rest of the world. But with cargo ships visiting just four times a year, there's a huge delivery lag. It also works the other way around: Pitcairners can now shop online. And then wait. And wait some more. "You buy something on the Internet," Ray Codling tells me from a nearby wooden bench, "and it arrives four months later. You wonder: Now why on earth did I buy that?"

That afternoon, Andrew — tattoos, piercings and all — invites me to "mission control." Perched on his quad bike, we climb dirt roads to his house near the island's highest point. There, at an elevation of more than a thousand feet, sits the control center for Pitcairn's budding cyber world: It's a Mac desktop on a coffee table in his living room. Nearby sit small sorting boxes full of black pearls to create jewelry.

"I just got an order for a necklace," he beams. "Got the money this morning." "How?" I ask, staring out over his sprawling view of an endless ocean. "How do you think?" he snaps back. "Online banking, mate. The lady wired the money straight to my account."

Back at the wharf, waiting to cast off, I'm still feeling uneasy. The world needs another cyber hot spot about as much as it needs another ice age. But then I meet Jacqui Christian, who returned to her island birthplace a few years ago. "I wouldn't have come back if we were still so cut off," she tells me as I crawl into the Zodiac. "Having Internet was a huge part of my decision to return."

Her words remind me that many locals had lamented the loss of younger islanders to oversea opportunities and how there won't be many Pitcairners left to share stories with unless something happens. As Jacqui asserts, that something just might be the Internet.

Shoving off from Pitcairn, waving goodbye to Jacqui, it occurs to me the Internet may be the only way for the island to survive as a living, breathing culture. So yes, the world can now make Facebook friends on Pitcairn and order its souvenirs online. But to meet the island's residents, to hold its keepsakes — well, that still takes some effort. Not even the mighty Internet can overcome splendid isolation.