Ukulele: The Renaissance

Had I known my brother was afraid of sand, I never would have agreed to go to Hawaii with him. Really, why would someone afraid of sand come to Oahu two or three times a year? Where do you think they keep the sand? "It's not really the sand," he protests when I finally insist we stop at the curved shoreline of Kailua Beach. "I just don't like all that sun." Yet, at the edge of the parking lot, he holds his shoes like shields to protect him from the evil beach, and in under five minutes — still remarkably pasty- white and with no dread grains clinging to his toes — he's back in the car, aimed for the sand-free pali. And I have no choice but to join him or hitchhike. Then he springs the trip's second surprise: My big brother has been making all these Hawaii trips because he has taken it upon himself to become a master ukulele maker. Yes, ukuleles. Guitars that chain smoked when young, and so grew up stunted. A tiny step away from kite strings run across a shoebox. The Rodney Dangerfield of the musical world. Those ukuleles.

OK, I admit, when you think about the islands, you think Spam, coconut tanning lotion — and ukuleles. The ukulele, says Brittni Paiva, who won her first award from the Hawaii Academy of Recording Arts at age 15, "is one of those things you associate with a place. It will always be distinctly Hawaiian."

That's because the ukulele is the center of Hawaiian traditional music. Sort of. Depends on how you define traditional. The instrument — locals just call it the uke (pronounced "ook"; the correct pronunciation of the whole thing is "oo-koo-LAY-lay") — has only been around since the late 1800s, a local adaptation of four-string mini guitars brought to the islands by Portuguese cowboys. A couple changes — different tuning, some body modifications — and the uke was born. Exactly how quickly it caught on can be illustrated by a single fact: Back in the 1890s, Queen Liliuokalani herself, Hawaii's last reigning queen, composed what was likely the first great ukulele hit, called "Aloha Oe."

The mainland had a brief ukulele craze around World War I, but the instrument quickly faded away again until the 1950s. That's when Arthur Godfrey started playing ukes in his television show. "If a kid has an uke in his hands," Godfrey said, "he's not going to get into much trouble," cleverly leaving out the fact that other kids would probably beat him up.

Fads, of course, pass, but this one had some staying power. By my late-'60s childhood, my friends and I knew exactly three things about ukuleles: First, you could buy one at any toy store for 10 or 15 bucks. Second, the strings tuned to the sentence, "My dog has fleas." And third, the only thing the ukulele was good for was Tiny Tim squeaking out "Tiptoe Through the Tulips With Me" or Don Ho crooning "Tiny Bubbles."

Fast forward four decades to my brother and me on Kailua Beach. He pops a CD into the car stereo and says, "Just listen." I have a brief, horrible flashback to our different tastes as teens — me using the Sex Pistols to drown out his country albums. But then the music starts up, soft and intricate; it sounds like a skilled flamenco player getting ready to show off. The tone is deep and rich. It swings. I'm nodding along, tapping my toe, getting into it, and after a couple tracks, I say, "OK, so when does the ukulele come in?"

"That was all ukulele."

A couple years pass, and now my brother and I again find ourselves together on Oahu. Maybe it's not entirely strange that I'm more curious about this whole ukulele thing. After all, as long as he's around, I have all this time normal people would spend on the beach. But first, before I fully fall down the uke rabbit hole, I have to check just one thing with Roy Sakuma, founder of the Ukulele Festival of Hawaii and a man who's been teaching the instrument in Honolulu for 40 years. I ask him my straightforward question: "Was Don Ho a good musician?"

"I don't know," Roy replies. "Was Frank Sinatra a good musician?" Oh. OK. Admittedly, 40 or so years ago, even in Hawaii the uke began to be seen as a toy as the rise of rock 'n' roll drove interest in the guitar. But now the islands are in the middle of an ukulele renaissance. Thousands of locals and tourists show up at the annual festival, uke acts dominate the Hawaiian Music Awards, and grade schools have classes in the instrument.

And forget buying an uke for a $20 bill. "Our entry model is $440," says Alan Okami at KoAloha Ukuleles. That price point, hovering around half a grand, holds true across the islands' uke makers. A high-end, customized uke can cost 10 times that.

KoAloha is maybe a typical story of how someone gets into making ukuleles: whim and eccentricity. Pops Okami was running a plastics company when legendary ukulele player Herb "Ohta-san" Ohta urged him to craft the miniature instruments. Pops spent the next six months using jewelers' tools to build an ukulele that measured under 6 inches long and that could be played by anyone with hands small enough to play a 6-inch uke. From there, he decided to start making the real thing. Pops drafted his sons into the fledgling business and now, a dozen years later, is running Hawaii's second-largest ukulele factory.

The true, classic ukulele is made of koa, a species of acacia tree endemic to the islands. Live koa trees are huge and scrubby; they grow fast and have a loose-bouquet silhouette that seems more African than Polynesian. The wood from the tree ranges in color from satiny light brown to almost black, and sometimes, for no apparent reason, "curly" koa develops, which, as the shop's luthier Paul Okami says, "looks like a hologram, the way the grain shines."

Stepping into the KoAloha workroom, I discover koa has its own smell, too, like ocean salt mixed with freshly turned earth.

But koa has its downsides: It's expensive since most of the koa trees in Hawaii are in protected forests; and from an acoustical point of view, it's very stiff, limiting the instrument's resonance. "Western red cedar is much better for sound," says Joe Souza at the windward side's Kanile'a Ukulele, where he makes both stock koa and custom instruments. "Or a lot of builders simply use Sitka spruce," the same wood that goes into quality guitars. Players seem to split into two camps: the ones after resonating sound, and the ones who say, "you want that, just play guitar," sneering at any uke not made of koa.

Oahu factories like Koaloha, Kanile'a and Kamaka dominate Hawaii's ukulele market, but perhaps the most innovative ukes come from people like my brother, working in garages after their day jobs. And these people, from as far away as the East Coast, Japan and beyond, come together for the annual Ukulele Guild of Hawaii exhibit to see and be seen.

My brother brings me to the show, where he stops dead in front of a pair of instruments: one with an elegant scoop at the neck and a fret board with grain that looks like echoes of Van Gogh's Starry Night, the other inlaid so it looks like a corner of the wood is peeling back, revealing a pale blue heart. While he gawks, someone hands me a rare bass uke, a thing of true beauty, feather light, smooth as satin. My fingers jam up on its neck, the size of a fat ruler, looking for the upright bass notes I've spent years teaching them. Soon, though, I scale down, and the uke sings low for me, thumping out a blues line that should be impossible for an instrument that's not much bigger than a loaf of bread.

Showing it to my brother, I tell him, "Make me one of these." He just snorts derisively, but because he's a very good brother, he's soon looking for tips from builders.

In the meantime, I reluctantly give the uke back. I have a fear of tools, a fear much more sensible than my brother's fear of sand — the last time I used a wrench, I somehow managed to set my hand on fi re. That's why I move away from discussions of saw blades and technical specs and instead start watching a couple guys blast through a killer arrangement of Pachelbel's "Canon in D Major." Classical uke. Who'd've thunk it?

Still, when they're done, I have to walk up and ask why they aren't playing "Stairway to Heaven " on a Stratocaster like normal people their age. It turns out, they could be; they both play a half-dozen instruments. But "the uke is our passion," says Daniel Nakashima, the older of the two, having just started college. "I wouldn't mind playing this instrument for the rest of my life. Show others a part of me."

Daniel's friend, Chris Salvador, agrees with him. "There's sort of an ukulele revolution now," Chris says. And both guys tell me that they would like to build their careers from the ukulele.

That night, at the Guild-sponsored performance of up-and-coming musicians, Chris gets on stage like it's the only place he can imagine being. "This is my own arrangement of 'Chopsticks,'" he says, checking his uke's tuning. "Don't be afraid to enjoy it." When he's done, I practically clap my fingernails off. I know I have seen the future.

Come morning, I drop off my brother at the airport for his long flight home. Finally free from his sand phobias, I decide to head straight to the North Shore to sit on the beach for a while. Near Ka'ena Point, I leave the car at the end of the road and hike until I'm alone with Hawaii, wallowing in soft sand, all this glorious sand, stretching away, lost in wind and wild water.

But then, instead of simply melting into it and roasting myself until I add a couple hundred more freckles to my skin, I find myself trying to hear the island's natural song. When the first people came to Hawaii, their music was entirely percussive, this sound of ocean imitating thunder as it meets the shore, and the brushed cymbal of afternoon rain deep in the pali.

Cursing my brother only slightly, I realize that I'm not done with the uke quite yet. Instead, I think I've fallen for it just like he did, just like the Hawaiians have. And yet that still doesn't really answer the big question of why they fell for this instrument to begin with.

In my further research, I meet Manu Boyd , the leader and ukulele player in the Grammy-nominated group Ho'okena and a recognized authority on Hawaiian traditions. "In an oral culture," he says, "the emphasis on the spoken, chanted, sung word was very important. The hula and the dances, both formally and informally, were physical embellishments of the words, accompanied by the pahu-hula — sharkskin drum — and the ipu — made of gourds."

Therein lies the trick: A classic koa ukulele can be played almost like a percussion instrument. As Boyd says, "The drumming patterns of the ipu were aligned with the ukulele." To show me that himself, Boyd reaches over and grabs an ipu gourd drum and begins to demonstrate the basic motif of Hawaiian music, the kahela. To me, it sounds like boom, boom, chicka, thud, repeat. That rhythm, he says, is intrinsic to the native language itself. "Whether it's chanting or singing, there's something about the fluidity of Hawaiian," Boyd says. "It's just beautiful."

If you want to hear someone sing in Hawaiian, I'm told, you go to Aunty Genoa, flowers in her hair, ukulele in her hands. Genoa Keawe's career goes back to the church choir when she was a child. She went on to play for the troops before World War II and made her first recordings in 1946. For Hawaiians, she practically defines local music.

And so I count myself incredibly lucky to have the people from KoAloha invite me to join them at Aunty Genoa's 89th birthday celebration. Everyone had been a little worried — Aunty has been ill recently — but tonight she's all charm, and I'm pretty sure when I shake her hand, her fingers are stronger than mine. A handshake isn't good enough, though. "Kiss me," she says, offering her cheek. "It's the island way."

In my life, I've met two perfect individuals: the Dalai Lama and my own Aunt Jessie. Just on the strength of this moment, I'm ready to put Genoa on the list. I don't know it at the time, but this will be our only meeting, and, as it turns out, one of her last performances. She dies peacefully in her sleep only a few months later, going, I'm sure, with a smile on her face and her fi nal heartbeats sounding like a skillfully played ipu.

On this night, though, she's nothing but smiles. Over the next four hours, what must surely be every famous musician in Hawaii performs just for Aunty and those sharing this moment with her. The music only pauses while Paul Okami from KoAloha presents the birthday girl with an uke he made of koa taken from old church pews.

At last, pushing midnight, Genoa Keawe herself gets up to play. I'm the only person in the room who doesn't know what to expect, but how could anybody expect this? In her signature song, "Alika," sung in an achingly high, clear voice that goes back to some of the earliest Hawaiian chant styles, Aunty holds a single note for well over a minute, while she gently strums her uke. All the singers around her, a third her age, turn blue and fall gasping as they try to imitate her.

Then for the exclamation point, Aunty takes a breath and does it again. Just a couple days ago, I was stupid enough to ask if uke players were really good musicians.

As penance, I head to the record store and start stocking up. I buy work not only from the players I've been meeting, but Herb Ohta , the Ka'au Crater Boys, Taimane Gardner. And, of course, the one uke player I could have named before I came: Israel Kamakawiwo'ole, "Brudda Iz, " the 700-plus-pound man with the voice of every angel who isn't otherwise occupied dancing on the head of a pin. Iz's "Over the Rainbow/What a Wonderful World" rendition was a mainland hit, I think, because he kept the song pretty yet still made it hurt; he made you feel that "Why, oh why can't I?" in a way that Judy Garland wasn't allowed to try.

In the years since he died, in 1997, his CDs and videos have made the shelves of every gift shop, and it's impossible to walk down Waikiki Beach without hearing a dozen imitators. Iz is kind of taken for granted, as reassuring as the afternoon wind headed offshore, as much a fact of life in Hawaii as the color of the ocean.

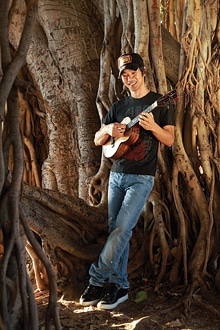

But Iz was really an old-fashioned player, strumming gently. Jake Shimabukuro — though you only use his first name, just like Elvis — is something different. He's my final stop to understand the uke, because each conversation I've had about the instrument in Hawaii has ultimately led to Jake.

"I'm sorry about that," Jake says with an embarrassed smile when we meet on his break from a recording session. Then he tells me the best thing about playing the ukulele: "When you're doing shows, the audience has such low expectations, you have nowhere to go but up."

Despite the clear lack of rock 'n' roll ego, at age 31 Jake Shimabukuro has revolutionized ukulele playing, taking it out of the band and turning it into a solo instrument. Along the way, he is ensuring that every teenager in Hawaii now wants to be like Jake. He's put virtuoso technique in service of music, stretching across genres, taking time along the way to record with Ziggy Marley and Béla Fleck & the Flecktones, and to headline at the House of Blues. His cover of George Harrison's "While My Guitar Gently Weeps" went viral on the Internet. If everybody from Don Ho to Iz strummed uke like a pleasant Sunday drive, Jake's finger-picking style is like a rocket car on steroids.

"Growing up," Jake tells me, "I really wasn't aware of all the different styles. I just heard the music."

So I have to ask him why the ukulele seems to tie together Hawaiian culture. "You'll see families come with their little kids, and high school students, and young adults, and grandmas and grandpas. People from all walks of life can relate to it." He laughs. "Bringing the masses together, that's the power of the uke."

OK, but there must be more. Jake's the king of the uke, so surely he has a reason why my sand-frightened brother returns to Hawaii again and again to learn more about the instrument. Surely he knows the answer to why the ukulele has sucked me in, why I'm now buying instructional videos and chord books. Or even insight on my most desperate question: Why am I chasing down ukulele makers and players when I could be spending my days on the beach watching women in black bikinis?

"From day one," Jake says, "you can already play a song on the uke. It's relaxing, it's meditative, and it's not intimidating. There's so much stress, we need some kind of outlet."

Great, but there must be even more. I keep pressing Jake. How has this instrument, this echo of wind in the pali and waves on black rocks, come to be the center of a Hawaiian music revival, a cultural icon?

Jake just shrugs, and then gives the best answer possible, one of simple joy: "I don't know," he says, "I really just like the plinky sound it makes."

Listen: To hear samples of ukulele music, check out these Hawaiian artists: Jake Shimabukuro, Brittni Paiva, Genoa Keawe, Israel "Iz" Kamakawiwo'ole.