Grenadines: Magazine Articles

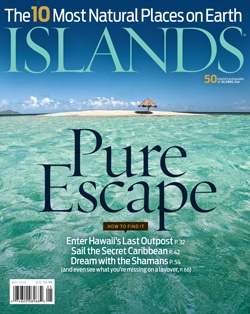

The ISLANDS editors present our latest articles on St. Vincent and the Grenadines, with photos, stories and information to inspire you to take your perfect trip to one of the best islands of the Caribbean.

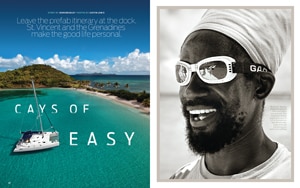

|Feature: Grenadines Sailing Join writer John Bradley and photographer Justin Lewis on this relaxing Moorings charter island-hopping in the Grenadines. Exclusively in the May 2010 issue.|

April/May 2010|| | | ||

|Intimate Escapes: Private Petit St. Vincent See how romantic this private-island resort is, from the luxury cottages to the Caribbean scenery and much more. See the map and article. |

Jan./Feb. 2009|| | | || | | |