Cuba: Young Man And The Sea

I slip over the side of the skiff, fly pole in hand. The soft, muddy bottom sucks at the skate shoes I use for wading. Four stingrays glide ahead of me. Behind me, a cloud of dark water marks my path through the shallows. A catshark, 4 feet long, ignores my approach, lazing in the warm water. Only a jab from the end of my fly pole keeps me from stepping on him.

"There," says my Cuban fishing guide, Keko, pointing at the water ahead of me. "Short cast. Eleven o'clock. Now!"

I cast my fly. A bonefish, one of the most difficult sport fish in the world to catch, finds it. He starts stripping line from the reel. I put the tip of the pole just above the water and then let him run. And run. Yards of line zip out across the mirror surface. The bone, catching his breath, stalls. I reel quickly, the tip of the pole bending in half. The bone runs again. My knuckles, already bruised and bloody from several days of fishing, smack the reel handle as it unspools 60 yards of line. I yelp in pain. The bone escapes. Keko says, "Tip up," as he shakes his head in disgust. If Hemingway were watching me, I'm sure he'd do the same. That thought is much more devastating than losing the bonefish. After all, I'm not here in the Jardines de la Reina, a pristine archipelago about 50 miles off the south coast of Cuba, just to fly fish. I'm here to fish as Papa did. My confession: I'm a closet Hemingway freak.

I've trekked the Hemingway trail for the better part of three decades. It's a passion I seldom mention because, frankly, Ernest Hemingway has not been in fashion, particularly with women, for about 50 years. It's bad enough to admit you like his novels (typical reaction: a bemused smirk), let alone admire his life as a work of art. But I am undeterred. Have I lived in a dingy apartment on the Left Bank in Paris, drinking cold Sancerre wine at well-lit places like Closerie des Lilas? Of course. Sent a stream of bitter red wine down my throat from a Spanish wine skin during the running of the bulls in Pamplona? Like a pro. Hiked up to the snows of Kilimanjaro? Before I was 30. I've listened to the mad laugh of hyenas while sleeping in a canvas tent in the Serengeti, sipped prosecco at Harry's Bar in Venice and stood forlornly in a light snowstorm at his grave in Ketchum, Idaho.

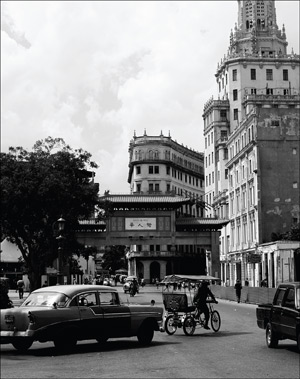

I've done it all — except walk his path in Cuba. That bothers me because you haven't completed a Hemingway pilgrimage until you've been to Cuba. This, for Ernest devotees, is Mecca. His body may be buried in Idaho, where he ended things in 1961, but his ghost resides in Havana. That's where he lived, loved and eventually fell apart — mentally and physically — during a 20-year stretch beginning in 1939 when he settled into a small hotel room and began penning For Whom the Bell Tolls. Knowing full well that the sun also rises — but only for so many years — I headed to Cuba. I stood on the balcony of room 511 — his room — in the Ambos Mundos Hotel in Old Havana. There I watched, as he did, the old women with their plastic bags of dried herbs coming out of Taquechel, the homeopathic pharmacy across the street. I spent a long afternoon at El Floridita, sitting at his spot in the corner of the dark bar. I ordered a daiquiri made Papa's way: white rum, lemon, sugar and six drops of maraschino. And I walked up the long, wooded path from San Francisco de Paula to the stylish villa of Finca La Vigía, where actress Ava Gardner swam naked in Hem's tree-shaded pool.

Over four days, I did all that and more. I peeked at the bathroom wall in his villa where Hemingway decided to scribble his daily weight changes (the notes for each date are still there 50 years later). I visited his favorite restaurant, La Terraza, in the fishing village of Cojímar, where he heard the tales that became the genesis of The Old Man and the Sea. After exploring Hemingway's Cuba all the way from one end to the other, I got on a boat to go fish among the islands in the stream. Which is where Keko and Jardines de la Reina — the Queen's Gardens — come in. Named by Christopher Columbus in honor of Queen Isabella of Spain, the gardens are a 100-mile-long saltwater wilderness where both Hemingway and Fidel Castro once fished. These days it is also a Cuban National Marine Park where commercial fishing is banned. An exception is if you're able to secure one of the rare and expensive berths aboard the Halcon, the 80-foot luxury yacht that once belonged to disgraced American fi nancier Robert Vesco. Castro confiscated it back in 1995 and turned it into a fi shing boat.

Operated by two Italians — Giuseppe Omegna and Filippo Invernizzi — the Halcon sleeps eight anglers plus a Cuban staff that includes a cook, a bartender, a divemaster and three fishing guides. For five days I fly-fish for bonefish, permit and tarpon. We also go spin casting for pelagic species like jack crevalle, yellowfin tuna, bonito and barracuda. Beyond the barrier reef of the Jardines, we troll deeper waters for horse-eye jacks, mutton fish, big groupers and monstrous Cubera snappers that can weigh more than a hundred pounds. We fish in the mornings and enjoy afternoon comidas, such as fillet of sheephead, jack crevalle sashimi, or squid in its own ink. And lots of cold Bucanero cerveza. Then the mandatory siesta, then five more hours of fishing, usually past dark. It's all capped by another enormous meal finished off with glasses of potent añejo (aged) rum and spicy Cohiba Esplendido cigars. We sit on the back of the boat and tell lies to each other while watching Mars chase Venus across the sky. Sometimes we go to bed at 3 a.m., sometimes much later. The next day is the same.

Yes, it is a manly man's adventure, a throwback to Hemingway's era. And I do catch fish. Lots of them. Courageous fish. Monstrous fish. Some so full of fight and life that I just have to let them go. There is no choice. I return to the flats. Keko is next to me again, with more of his simple directions: "Right. Again. More right. Shorter. There. Good." I cast out over another bonefish. He runs. And runs. I fight him for five minutes, then 10. He gives up before I do. Keko pulls the exhausted bone out of the water, unhooks it and cradles it. I'm flush, breathing hard. "Tu primera vez?" Keko asks. "Yes," I say. "My first." Keko nods. He slips the bone back into the water. As I watch it disappear, I know, finally, Papa would be proud.