Kauai: Surfing Safari

KAUAI: SURFING SAFARI

The numerous rivers around kauai get their start at the island's rainy center, Mount Waialeale, and fl ow down to the ocean like spokes in a wheel. One of them, the Hanalei River, runs through a stunning wildlife refuge where endangered Hawaiian waterbirds play. This day, I'm in the middle of the river, but I'm not looking up at the birds; I'm looking down at my feet — surfing. Well, sort of. Seemingly just like everybody else in Hawaii, I'm learning how to "stand-up paddle surf." I've lived here for more than eight years, and I've always wanted to spend more time surfi ng than wiping out. And yet the one time I actually managed to stand up on a traditional surfboard, my mastery lasted for a nanosecond before I went under. The rest of that day, salt water dripped from my nose at the most inopportune times.

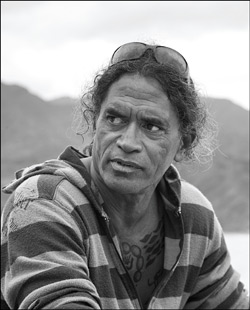

But I never thought my key to the waves would be surfing a river. While paddle surfi ng has been around for decades, it has only become socially acceptable lately, with everyone from pro surfers to celebrities trying it. Basically, to do it you stand on an oversized surfboard and use an elongated, canoe-type paddle to catch and surf waves. Of course, the ideas that sound the simplest are never the easiest to execute. I'm lucky my instructor is Titus Kinimaka, a legend of big-wave surfi ng. When I fi rst meet him in front of the surf shop in Hanalei that bears his name, he is standing at the top of a fl ight of stairs with his arms crossed. Unruly black hair striated with silver and sun-drenched with gold drapes his shoulders. His dark face is deeply carved, like the vista of Namolokama Mountain behind us, the result of his years spent in wind and water. He looks larger than life.

"Hi, I'm Kim," I say. He offers me his hand. "Titus." Even his name makes me feel small, and I'm close to 6 feet. This is someone who has conquered one of the hardest sports on Earth, riding some of the biggest waves on Earth. I feel like I'm just a school kid daring to ask Michael Jordan for dribbling tips. We drive from his surf shop to Hanalei Bay. There we check the surf, grab our gear and walk over to the adjacent Hanalei River. On the shore, Titus shows me where to stand on the board and how to paddle. I just have to fi gure out how to go from having my two feet fi rmly planted on the ground to having two feet shoulder-width apart on a fl oating board.

"Watch me," Titus says as he places one foot on the center of his board like he's about to climb a couple stairs. He steps up with his other foot and, easy as that, he is standing on water. I'm stalling, and Titus knows it. "So, I just step up?" I ask. "Try it," he says. I do, and I stand on water, too. The difference: I feel like a newborn colt, all legs and angles.

Titus is a fit 54; he learned to surf when he was 2. I am 45, and I've tried to surf traditionalstyle maybe three times in my entire life. Three days before this, Titus was on his stand-up surfboard carving the faces of 20-foot waves down the beach in one of the biggest swells of the season. He has paddled into waves that others merely admire from shore. He broke new ground with tow-in surfi ng, a style that uses a personal watercraft to pull him into fast-moving, behemoth waves. The biggest wave Titus ever rode broke a mile north of Hanalei at a place called King's Reef. He estimates the waves there can be up to 100 feet or so. That's the height of a 10-story building. I use elevators for buildings that tall. But Titus was also a lifeguard at one time, and while he's willing to risk his own life, blessedly, I discover he is not willing to risk mine.

We'll stay on the river," he says. The Hanalei River, which feeds into the bay, is perfect for learning this sport because its water is so fl at. A form of stand-up paddling may have been used in old Hawaii for fi shing, but its roots as a sport began in the 1950s when Waikiki surf instructors grabbed canoe paddles so they could head out to the surf standing up. That way, the cameras strapped around their necks stayed dry, and they could take close-up pictures of their students. Stand-up paddling didn't take off, though, until the past few years, thanks in part to how easy it is to learn compared to regular surfi ng supposedly. Standing on my board as it fl oats on the placid river, I take a couple tentative strokes. Titus tells me to plant my paddle's entire blade in the water, so I reach forward, bending at the waist — big mistake — and immerse my paddle. Immediately, the board slips out from under me, and I'm treading water in a cold river. Hovering over me like a king atop his surfboard, Titus smiles. "I was trying to keep you dry," he says.

I slither back onto the board, slide my knees under me and stand back up. Once I have the fi rst fall out of the way, I settle in. Soon I even feel comfortable paddling. Two strokes on one side, then two strokes on the other.

Now it's time to learn to turn. "You've got to be able to turn quickly, so you can catch the next wave," Titus says. He demonstrates, digging the back of his board into the water and swiveling it around like a screw. He instructs me to slide my strong leg back when I want to turn. That will make the board's nose pop up, a maneuver that will be useful when I'm ready to whip around on a regular surfboard and ride a wave. My turn, though, isn't as commanding. In fact, it takes nearly a dozen tries and as many cold plunges in the river before I make a complete turn. Then I try turning the other way, and I whip my board around on my fi rst attempt. Titus' eyes open wide. "You've got some skills now," he says. "You keep practicing in the river, and in a couple weeks, you'll be on the ocean. In a year, you'll really be riding some waves." Maybe then I'll go from feeling like a newborn colt to a ballerina.

As Titus and I walk with our boards in the crooks of our arms, I notice he is no taller than I am. He tells me he was surfi ng last night past sunset, and he was out again today before dawn. "I love surfi ng," he says. "I live and breathe surfi ng." That's when I realize Titus isn't just teaching me to surf. He's teaching me something else. Something about practice. Patience. Persistence. I may not have actually surfed waves today, but if I keep trying, I will eventually. "Thank you," I say, leaning in to give Titus a hug goodbye. "Come down any time," he says, pursing his lips and brushing my cheek with a kiss. "Take a board out. Practice." And I want to. I want to come back, try again. Some day, I know I'll even surf waves, but defi nitely not the size Titus surfs — no, thank you.

Until then, I can paddle the river, looking for those endangered seabirds. I can paddle along the coast with the wind at my back, catching little bumps of waves. I can explore places on my island home that I've never seen before. I moved to Kauai because my husband and I fell in love with this island on our honeymoon. I've since hiked the Kukui Trail and dived the Makua Beach lava tubes countless times. Now with board under feet, I'm ready to fall in love with Kauai all over again.