Bizarre Facts You Probably Didn't Know About The Grand Canyon

Snaking through the wild heartlands of northern Arizona, the world's most dramatic canyon is grand in name and grand in nature. Carved over millions of years by the Colorado River and ancient geological processes, the Grand Canyon has an average depth of 1 mile and stretches a whopping 18 miles between rims at its widest point. This vast spectacle of sheer cliffs, colorful rock layers, and dramatic plateaus is all very impressive, but did you know that the Grand Canyon hides several bizarre secrets that surprise even regular visitors?

The Grand Canyon receives almost 5 million tourists a year, making it one of America's most-visited national parks. Yet most travelers don't realize that the famous canyon has links to the Cold War and was once the setting for an elaborate ancient Egyptian hoax. This remote wonder of nature is so isolated that pack mules are still used to deliver mail, and real-life monsters have been spotted roaming around the canyon's rocky deserts.

In this article, we'll reveal a series of strange facts that only add to the appeal of this legendary national park, with penis worms, unexplained disappearances, and 40,000-year-old sloth dung all playing a part in this alternative tale of the Grand Canyon. You'll view the park in a new light after learning about these bizarre myths and mysteries, and on your next visit, you may even experience some of them for yourself.

The Grand Canyon sits on bizarre fossils like penis worms

While you won't find dinosaur fossils at the Grand Canyon — the rocks here are older than these legendary creatures — you might come across something even stranger. In 2023, a team of scientists led by paleontologist Giovanni Mussini from the University of Cambridge discovered the fossilized remains of several weird soft-bodied creatures while rafting through the canyon.

Among these fossil finds were mollusks that scraped algae off rocks with teeth shaped like mini shovels, and hairy-limbed crustaceans with molar teeth. Yet the most monstrous of these ancient marine invertebrates was a phallus-shaped critter with a retractable tooth-lined throat, aptly known as a penis worm. Named Kraytdraco spectatus thanks to its resemblance to the giant burrowing dragon from Star Wars, this strange, toothy worm was an opportunistic feeder, devouring anything that stumbled across its path. Measuring up to 8 inches long, these freaky worms inhabited the area over half a billion years ago, with some living in shells like modern-day hermit crabs.

Fossils provide fascinating evolutionary snapshots of early life, showing what the Grand Canyon landscape may have looked like and the type of creatures that lived there long ago. The discovery of fossilized penis worms and other bizarre marine organisms is important because it demonstrates that the Grand Canyon region wasn't always as arid as it is today; in fact, it was once submerged beneath shallow water.

The Grand Canyon has snow in winter

Although summer temperatures at the bottom of the Grand Canyon sometimes exceed 100 degrees Fahrenheit, this semi-arid park experiences snow during winter. On the canyon rims, precipitation often falls as snow between November and April, but lower down, where it's warmer, this turns into rain. The higher and wetter North Rim averages 142 inches of snow a year, with the lowest recorded temperature plummeting to an icy -22 degrees Fahrenheit in 1985. In fact, there can be so much snow on the North Rim that roads and trails here are usually closed for the winter season. A bizarre concept for somewhere that's often so hot. It snows far less on the South Rim, which averages 58 inches of snow a year and generally remains open throughout the winter.

For many visitors, winter may not seem like the ultimate time to plan a trip to the Grand Canyon, but traveling at this time of year does have its benefits. Roads and trails on the South Rim are quieter, accommodation prices tend to be cheaper, and the landscape is perhaps even more beautiful, with the snow-dusted rims and rock buttresses contrasting starkly against the canyon's colorful rock layers. Most visitors remain on the rim, using the shuttle buses to take in the winter views from scenic overlooks. If you do decide to hit the trails, be aware that the upper reaches of the canyon can be icy, so shoe spikes and trekking poles are recommended.

People have lived down in the Grand Canyon for centuries

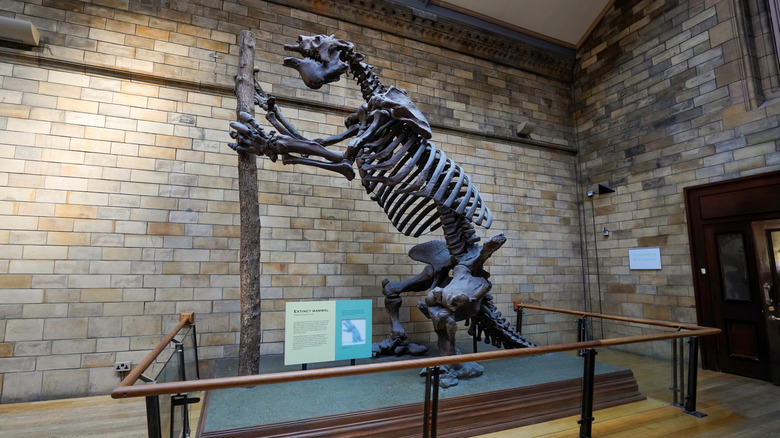

At first glance, the Grand Canyon seems like an improbable place to live, with its arid ravines and steep cliffs historically deterring all but the most intrepid of explorers. Yet artifacts like stone tools, charcoal, and pottery discovered in the canyon prove that it has been occupied by humans for at least 12,000 years. The first canyon residents were likely nomadic hunters, subsisting on animals like bison, mammoths, and ground sloths, as well as foraged plants, while living in rock shelters. Over the centuries, the warming climate led to agricultural experimentation, allowing for more permanent settlement in the canyon.

Today, there are 11 Native American tribes with ancestral ties to the Grand Canyon region, including the Havasupai, Hopi, and Navajo. The Havasupai Tribe has lived inside the canyon for more than 1,000 years. Known as the People of the Blue Green Waters after the life-giving aquifer that sustains the village of Supai, these canyon inhabitants live in one of the remotest locations in the world. It's an 8-mile trek to reach the canyon rim and the outside world.

Most travelers just visit Grand Canyon Village inside the Grand Canyon National Park on the South Rim, but if you're up for an adventure, you can hike down to Supai Village and stay overnight in the lodge or campsite. You'll need a permit to visit — these are granted only by an annual lottery held in February, so access is all down to the luck of the draw.

Mail is delivered by mules to a village in the Grand Canyon

Modern transport and communication systems are no match for the ancient topography of the canyon, which remains vastly impenetrable even today. However, where human invention fails, the traditional mule succeeds. The United States Postal Service (USPS) still uses mules and pack horses to transport mail along the 8-mile trail to the village of Supai, down inside the Grand Canyon, where a community of around 200 people lives. It's bizarre to think that no other mail solution has been found, and it's unsurprising to learn that this is the last such service in the country.

Horses and mules have right of way on the canyon trails, so if you encounter them on your hike, step to the side and allow them to pass. Keep your camera handy as the mule mail train is a spectacle to behold, with a long line of pack animals plodding diligently up the switchbacks, led by riders in cowboy hats and chaps. At the top of the trail, the post rider hands the outgoing mail to a driver for transport to the nearest post office, then collects any incoming letters and parcels for delivery back down to Supai. The 16-mile round-trip takes six hours, with the USPS mail train running five days a week.

If you're visiting Supai Village and don't fancy the long hike down, you can hire a pack horse instead and get a taste of mule train life. Once in the village, many people like to send a postcard from Supai, which will be marked with a special Mule Train Mail stamp. Remember to take some cash, as only one store accepts credit cards.

Grand Canyon caves were Cold War bomb shelters

During the nuclear tensions of the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962, the Grand Canyon Caverns were designated as a fallout shelter by the U.S. Government. This extensive cave network lies 210 feet below ground and is known as the biggest dry cavern system in the country — it was the perfect place to shelter during a potential catastrophe.

There was enough room down in the caves for around 2,000 people to hide out during a bombing, with food and water resources that would last a couple of weeks. There were portable toilets too, but with just three rolls of toilet paper provided, it's a relief in more ways than one that the crisis thankfully passed and the subterranean shelter was never needed. The survival supplies remain and can still be viewed on a tour of the caverns today. According to Reddit users, there's also a mummified sloth that can be seen down in the caves.

The Grand Canyon Caverns are one of the region's most bizarre tourist attractions. While cave tours are one of the main draws, there's also a unique underground canyon dining spot where you can enjoy an intimate meal before returning to the surface. The atmospheric Crystal Restaurant sits in the largest cavern and offers 360-degree views of the vast chamber from your table. Daring explorers can sleep 221 feet underground in a cave suite that comes complete with its own ensuite bathroom, although this is often fully booked as it's such an unusual experience.

A cave full of sloth dung holds Ice Age secrets

During the mid-1930s, a team of archaeologists and geologists discovered huge piles of fossilized sloth dung in the Grand Canyon's Rampart Cave, leading scientists to speculate on the reason for the extinction of one of the most iconic Ice Age mammals. The unusual dung deposits lay several feet deep with older layers dating back 40,000 years, confirming that the sloths used this chamber on the western edge of the canyon for many generations, perhaps as a nursery since many of the bones found here belonged to youngsters. It's extremely dry inside the cave, which is why the sloth dung has been so well preserved.

Shasta ground sloths were once found across much of North America during the last Ice Age, but became extinct around 11,000 years ago. The cause wasn't clear until the findings from Rampart Cave shed new light on the plight of the sloths. Plant fossils found in the petrified scat showed that there was plenty of vegetation around to sustain a sloth population in the Grand Canyon, yet these animals disappeared without explanation. It's therefore likely that it was overhunting by humans rather than climate change that led to the demise of the Shasta ground sloth. Sadly, in 1976, vandals broke into Rampart Cave and set fire to the deposits, destroying around 70% of the pile. Today, some of the surviving fossilized sloth dung can be found in the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History.

The Grand Canyon was the setting for an ancient Egyptian hoax

Nearly 7,500 miles separate Arizona from Cairo, but that didn't stop the Grand Canyon from becoming the center of a bizarre hoax involving ancient Egypt back in the early 20th century. On April 5, 1909, the Arizona Gazette reported that an explorer named G. E. Kinkaid had discovered a vast underground citadel in the Grand Canyon with hundreds of cave rooms containing artifacts linked to ancient Egyptian civilizations.

The Gazette asserted that the Smithsonian Institute had funded the expedition, and that the archaeologists had "made discoveries which almost conclusively prove that the race which inhabited this mysterious cavern ... was of oriental origin, possibly from Egypt, tracing back to Ramses." The article in the Gazette goes on to say that many objects found inside the caves indicated a mysterious connection between Egypt and the Grand Canyon. Items such as war weapons, broken swords, mummified relics, idol carvings, gold cups, pottery cases, and tablets covered with strange hieroglyphics were all reported to have been discovered.

However, this imaginative tale was later revealed as a hoax by the Smithsonian Institute, which said there was no truth to the story and doubted that Mr. Kinkaid ever existed. Despite this, the myth surrounding the legend lives on. Was this a late April Fools' joke that got out of hand, or a grand cover-up by the Institute? We'll leave you to make up your own mind.

A billion years is missing from the Grand Canyon's geology

The Grand Canyon is a geologist's dream. Designated a National Park in 1919, the canyon subsequently became a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1979 and has been attracting the attention of scientists and researchers for centuries. Yet even the most learned experts are baffled by a bizarre billion-year gap in the canyon's rock record. Known as the Great Unconformity, these missing rock layers were eroded into thin air, but no one really knows why. It remains one of the greatest geological mysteries of all time.

Alongside its vastness, the Grand Canyon is famed for the colorful rock layers, which represent 2 billion years of history. Over time, horizontal tiers of sediment were deposited chronologically, with the oldest rocks at the bottom. It's these vertical layers that tell us about the region's geological timeline and what the environment was like at any given point, with each layer representing a specific period in the Earth's history.

However, after determining the ages of the different rock layers in the canyon walls, geologists discovered that around 1.3 billion years are missing from the record. This unconformity is unusual, although not unprecedented, as similar unexplained geological occurrences have been observed in rocks all around the world. Scientists at the University of Colorado in Boulder have suggested that tectonic upheaval was the likely culprit, with rifting and faults probably leading to erosion of the exposed rock sediment layers. Yet no one knows for sure what happened to the missing layers, and investigations remain ongoing.

Some canyon explorers have mysteriously disappeared

The lure of the unknown and humankind's enduring quest to conquer inaccessible landscapes have been enticing explorers to the Grand Canyon for centuries. Some return home after a successful mission; others vanish into thin air. The most famous Grand Canyon disappearance occurred in 1869, during a scientific expedition led by American explorer John Wesley Powell. The trip was beset with disasters, like the loss of essential supplies and even a boat. Team morale was low, so Bill Dunn and brothers Oramel and Seneca Howland decided to make their way out of the canyon alone instead of risking the dangerous rapids ahead. The three men were never seen again, and their departure point is now known as Separation Canyon. Some believe they were killed by a Shivwits Native American war party, but others think the trio was murdered by Mormon settlers who mistook them for lawmen investigating the Mountain Meadows Massacre.

Meanwhile, in 1928, honeymooners Glen and Bessie Hyde disappeared during a river voyage through the Grand Canyon. Later, their boat was discovered intact and full of supplies, but the couple was nowhere to be seen. Speculations as to their fate were rife and ranged from a murderous quarrel between the spouses to Bessie possibly reappearing years later on the same river. More recently, modern-day explorer Floyd E. Roberts III vanished during a 9-day hike in 2016, which coincidentally was planned to end in Separation Canyon. Having split from his group after agreeing to meet up on the other side of a hill, Roberts disappeared without a trace.

Real-life monsters have been spotted in the Grand Canyon

Monsters, both mythical and real, have been linked to the Grand Canyon, and it's possible you might even see one on your next visit. The Mogollon Monster is the canyon's version of Bigfoot, with multiple sightings reported in the state since the early 20th century. While Bigfoot is said to roam the mountains of the Pacific Northwest and sometimes the forests and Tribal Lands of California, the Mogollon Monster is apparently native to Arizona. It is named after the Mogollon Rim, where it was first spotted. This hairy creature is said to be about 7 feet tall with foul-smelling breath.

In 1903, The Arizona Republican reported that a man named I. W. Stevens had seen the monster feeding on the carcass of a cougar near the Grand Canyon. He said the creature emitted "the wildest, most unearthly screech you could imagine," which caused Stevens to flee the canyon. While this reclusive monster is considered a cryptid, stories of encounters continue to capture the imaginations of those who visit the area, so keep your eyes peeled if you're hiking less-traveled, backcountry routes in the Grand Canyon.

Meanwhile, the Grand Canyon's very real gila monsters can be found in the western part of the national park. These large, venomous lizards were once thought by Native Americans to be desert dragons with breath that could kill, while in the 19th century, Mormon settlers harvested the oil from gila monsters, believing it had superpowers. Despite these legends, the elusive black and orange reptiles aren't as terrifying as you might think. Their toxic bite can be painful, but it's not life-threatening to humans, and if you do encounter one on the trail, it'll probably just scuttle off into the rocks.